Developing cost‑efficient In Situ and Ex Situ remediation strategies for soil, groundwater and marine sediments

“What factors do you need to consider in your decision‑making process for developing an effective cost‑efficient soil, groundwater and sediment remedial strategy?”

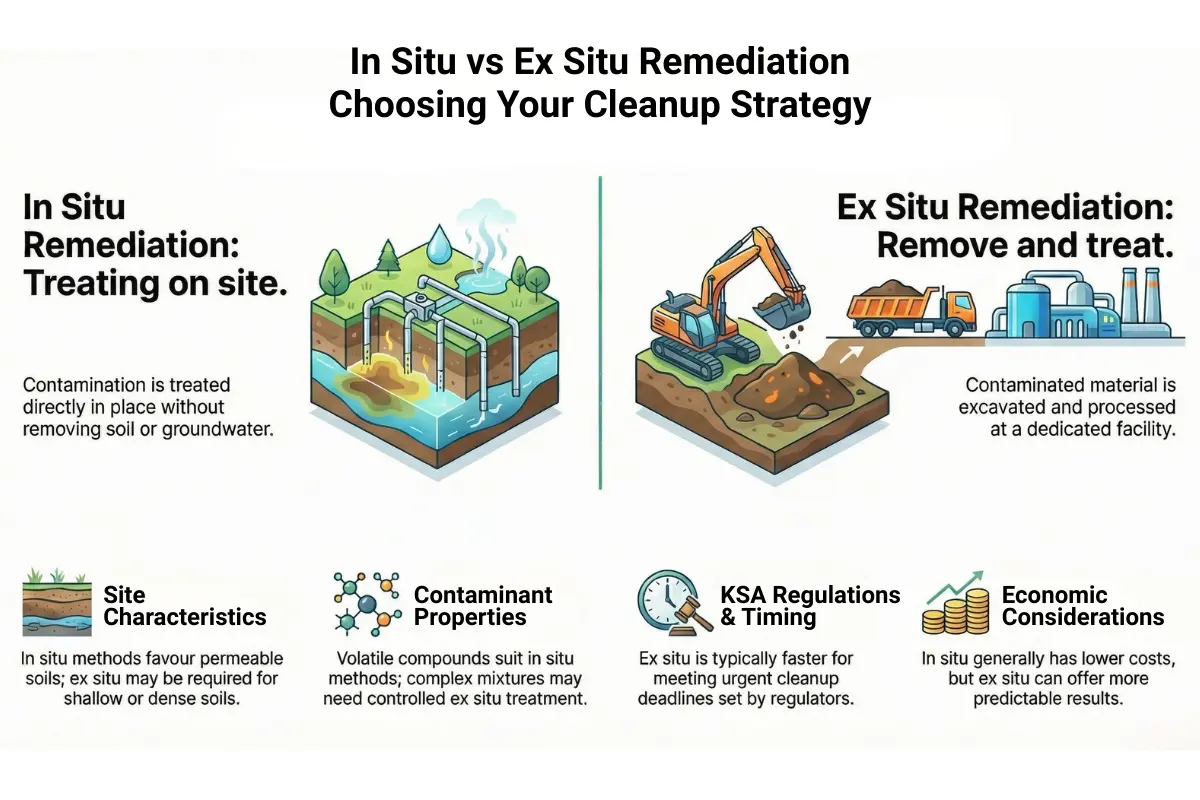

Selecting between in situ and ex situ engineering approaches depends on multiple interrelated and often interconnected factors that must be carefully evaluated, both technically and commercially, for each unique site situation. In the main, the key elements to be considered in your thinking process should include the following, namely: site characteristics, contaminant properties, regulatory requirements, economic considerations and environmental impact.

For Staterra, these decisions sit at the core of how environmental engineering and long‑term sustainability are integrated on oil and gas and industrial projects, as discussed further in our article on the relationship between environmental engineering and sustainability.

Key factors in selecting in situ vs ex situ

Site characteristics: soil permeability, depth to groundwater piezometric surface, and accessibility all influence the feasibility of one’s approach. In situ methods normally work best in permeable soils where transmissivity is greater than 1×10-41×10-4 or 10-51055 m sec-1-1, under which conditions air and nutrients (orthophosphate phosphorous [PO4]3 –[PO4]3 – and ammoniacal nitrogen [NH4-N][NH4–N]) can be easily distributed.

Ex situ methods may be necessary when contamination is relatively shallow (less than 4.0 m below ground level – BGL) or in low‑permeability soils where transmissivity is around 1×10-61×10-6 m sec-1-1 or higher, making it difficult to achieve consistent in situ treatment. Understanding these site characteristics is a fundamental outcome of the Phase I Desk Top Study for Contaminant Assessment and subsequent intrusive investigation phases.

Contaminant properties: some pollutants respond better to specific treatment approaches than others. Volatile compounds might be better suited for in situ methods that can capture vapours, while more complex mixtures may require the more controlled conditions of ex situ treatment.

This also applies to groundwater aquifer contamination, where petrol containing around 50% BTEX compounds has a much higher solubility maxima; for example, benzene (C66H66) has a solubility of approximately 1,200-1,400 mg l-1-1, whereas Number 2/4 run diesel has a solubility maxima approaching only 2-4 mg l-1-1. These differences in solubility and behaviour are critical when designing the Phase III bioremediation step of Staterra’s four‑phase remediation approach.

Regulatory requirements: MEWA, NCEC and/or RCJY cleanup standards and timelines for an effective clean‑up often dictate the kind of approach adopted. When rapid cleanup is required, ex situ methods typically achieve results faster, while in situ methods might be preferred for a longer‑term, sustainable cleanup strategy that can require more advanced technical engineering applications.

Staterra’s strategic perspective on these regulatory drivers and their impact on project planning is presented in our guide to a strategic roadmap for legacy waste assessment and remediation in Saudi Arabia.

Economic considerations: In situ methods generally have lower costs, both CAPEX and OPEX, due to reduced excavation and transportation requirements. However, ex situ methods may be more cost‑effective when considering total project duration and certainty in terms of expectations of results.

Environmental impact: in situ methods typically have lower environmental impact by avoiding the need for excavation and transportation of contaminated materials. However, ex situ methods may be necessary to prevent further contaminant migration or protect sensitive environmental receptors – both flora and fauna, marine and terrestrial – from contaminant exposure.

The most effective bioremediation strategies often combine a dual approach, utilising in situ methodologies for bulk contaminant removal on mass and ex situ techniques for treating the most heavily contaminated materials or achieving final cleanup standards, often aimed at target values of TPH of 1% or 10,000 mg kg.

In situ vs ex situ remediation

Exploring the types of remediation technologies currently available today as of 2025, the terms “in situ” and “ex situ” play a pivotal role in shaping the strategies utilised by blue‑chip petroleum hydrocarbon extraction and processing companies and their remedial SME consultants and engineers. In situ remediation methods are applied directly to the contaminated site without the requirement for removal of the affected soil and/or groundwater.

This approach includes techniques such as bioremediation, where aerobic carbonoclastic microbes degrade organic contaminants, or in situ chemical oxidation, which involves pumping oxidising agents such as hydrogen peroxide (H22O22) to enhance degradation of organic compounds directly within the groundwater aquifer in earnest. These methods feature strongly in Staterra’s Phase III bioremediation projects.

Conversely, ex situ remediation involves excavating or removing contaminated material from its original location. This removed material can then be dealt with elsewhere at dedicated facilities, often employing more state‑of‑the‑art intensive physical processes including thermal desorption and/or encapsulation and/or chemical fixation using pozzolanic or cementitious agents including Portland cement.

Ex situ techniques are particularly useful when the contaminated materials require isolation or when the contaminated site requires more rigorous containment and control methods. Both remediation strategies offer different advantages depending on the complexity and potential recalcitrance of the contamination, the nature of the contaminated area, and the urgency of remediation to deal with the contamination in question.

Soil remediation

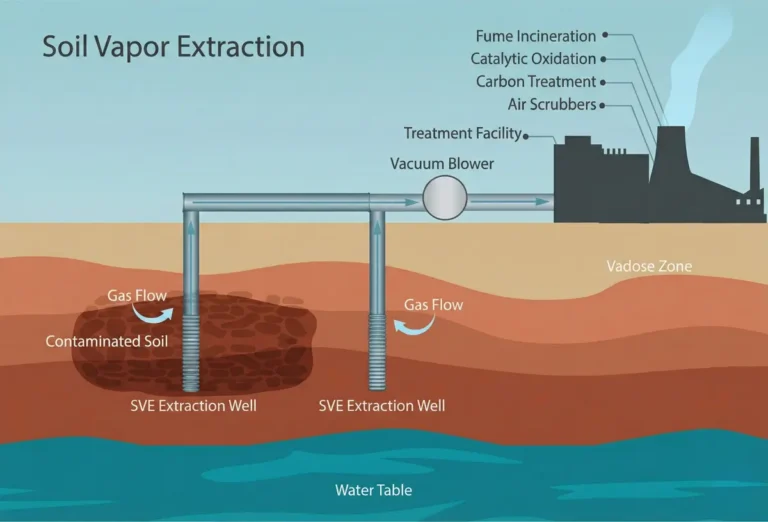

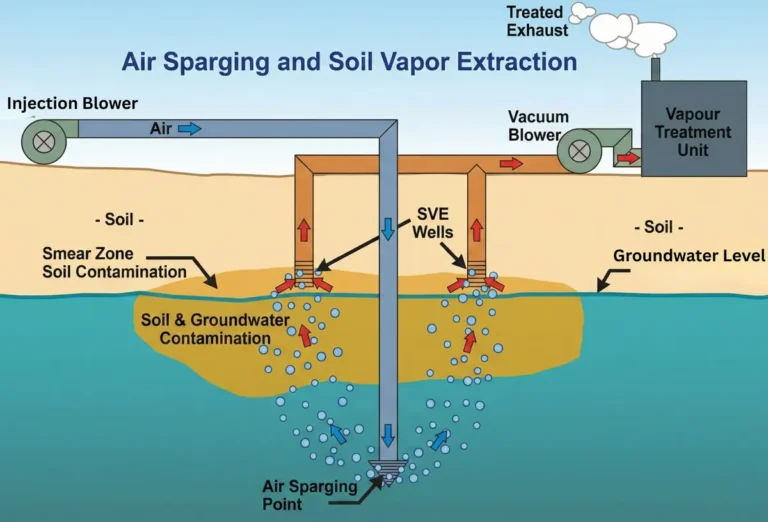

Soil contamination can arise from oil spills, leakages, oil and gas industrial activities, or the improper disposal of hydrocarbon‑based hazardous materials. Staterra utilises advanced remediation technologies to address these challenges, deploying methods like soil vapour extraction and pump‑and‑treat, which remove volatile and semi‑volatile contaminants from the soil.

This approach is highlighted and detailed in our Legacy Waste documentation produced according to the MEWA Executive Regulations for soil and groundwater protection (2025). The remediation process for soil often requires a detailed and extensive site assessment to determine the most effective method for removing contaminants while ensuring minimal impact on the surrounding environment.

Whether dealing with crude oil, legacy waste sludge, heavy metals, metalloids, organic DNAPL solvents, or other toxic chemicals, the ultimate objective is to restore the soil to a condition safe for residential, commercial, or industrial use. Safeguarding public health and supporting environmental sustainability is therefore the ultimate objective in any effective remedial strategy.

Groundwater remediation

Groundwater remediation is a critical aspect of environmental management, especially in areas with a history of industrial activity that has led to contamination. Various techniques ensure groundwater is treated effectively and restored to a safe standard for human consumption as potable water or for other beneficial uses.

The following are but a few examples of technologies often employed for groundwater restoration or clean‑up:

Pump and Treat: this tried and tested classic method entails pumping contaminated groundwater above ground, where it is more easily treated to remove pollutants including volatile organic compounds (VOCs), organic contaminants and heavy metals. Once cleaned, the water can be re‑injected into the ground or discharged to an acceptable receiving body of water or, best‑case scenario, recycled for irrigation or other purposes in line with the circular economy philosophy.

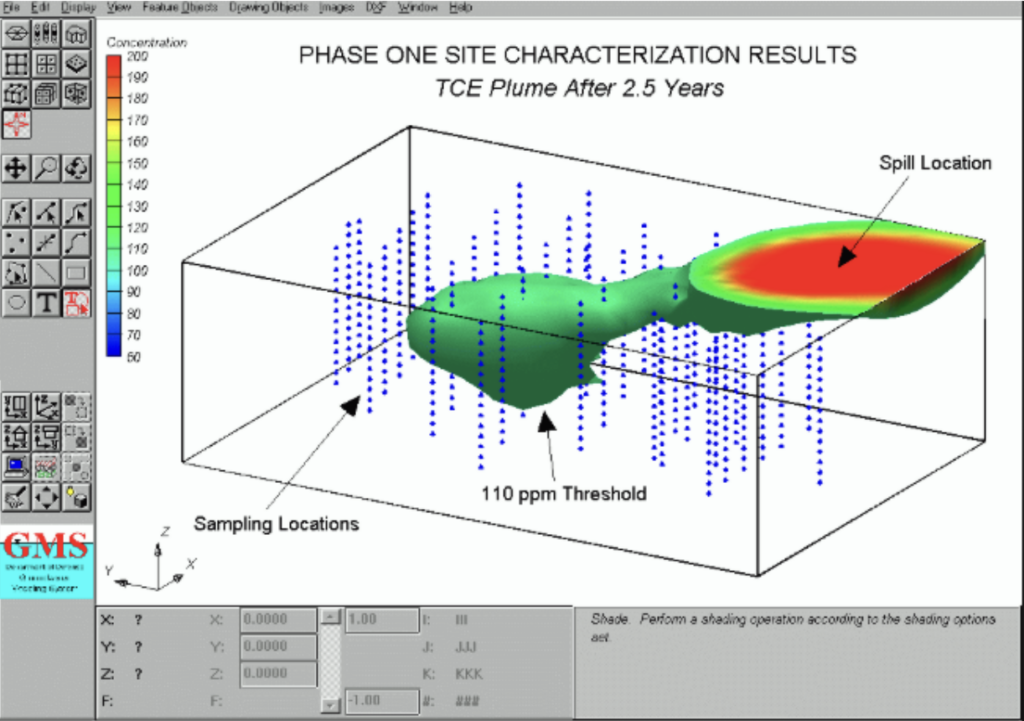

In situ chemical oxidation/reduction: this particular technique involves injecting reactive, normally oxidative chemicals directly into the contaminated groundwater to degrade toxic organic compounds through an oxidative chemical reaction. It is particularly effective for site‑specific targeting of contamination plumes in the X, Y and Z axes.

Air sparging: this innovative approach injects air directly into the groundwater aquifer in order to volatilise the contaminants and promote naturally indigenous site aerobic degradation. Air sparging is highly effective for removing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from groundwater.

Each technique offers its own unique advantages and can be tailored exactly to suit specific environmental contaminants and hydrogeological site conditions, making the remediation of contaminated groundwater a highly effective restorative action. Long‑term performance is verified as part of Staterra’s Phase IV soil and groundwater remedial monitoring and reporting, which focuses on plume behaviour, trend analysis and compliance assurance.

Marine sediment remediation

Marine sediment remediation is a crucial component of environmental restoration where pollutants may settle in the sediment upon the seabed or at the bottom of other water bodies. This process involves various techniques to address and neutralise contaminants threatening marine aquatic flora and fauna as well as human health.

Effective sediment remediation will ensure longer‑term sustainability of aquatic environments, thereby making it a key strategy in environmental protection engineering. Techniques commonly employed include the following:

Marine dredging: this methodology often involves physically and mechanically removing contaminated sediment from the sea floor. It is effective for large‑scale cleanup and when contaminants are heavily concentrated, but must be handled carefully to prevent further dispersion of pollutants into the benthic water column.

Capping: capping involves placing a barrier over contaminated sediments to prevent the spread of pollutants. This barrier, often made of natural or synthetic materials, effectively isolates contaminants from the surrounding environment, helping to contain the migration of hazardous pollutants (both TSS and TDS) and serving to protect overall water quality.

In situ treatment: finally, this approach can effectively address the contaminated sediment where it is located, eliminating the requirement for removal. Techniques such as bioremediation or chemical stabilisation – already addressed above – are used, and in situ treatment is a prerequisite for mitigating disturbances to the marine ecosystem, often favoured in more sensitive, inaccessible environs.

Conclusions

All the aforementioned remedial techniques offer specific bespoke strategic solutions for managing contaminated soil and groundwater, including marine‑based sediments, and are integral to maintaining aquatic ecological well‑being. Whether the choice is removal, isolation, or direct treatment, soil, groundwater and sediment remediation play a pivotal role in environmental restoration strategies for your consideration, ensuring the overall reduction of risk to environmentally sensitive receptors, both flora and fauna, terrestrial and marine, in the global environment today.

For further information or to discuss your site contaminant issues, contact Staterra today – we go “Beyond Compliance.”

Author: John David Lapinskas, C.Chem., C.Env. – Technical Director, Staterra Environmental Engineering